Photo Credit: City of Vancouver Archives.

Historical Timeline

To read more detailed accounts of our history, see Bartering with the Bones of Our Dead by Laurie Arnold, The Geography of Memory by Eileen Delehanty Pearkes and Swift River by Laura Stovel.

Table of Contents

European Contact and the Fur Trade

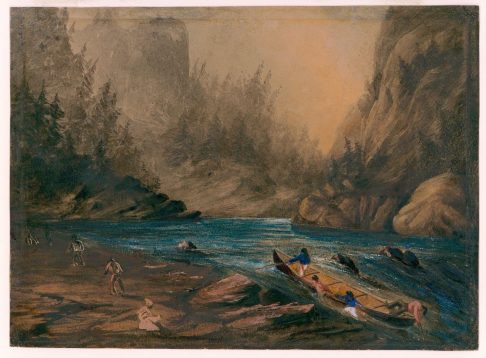

The British surveyor, cartographer and fur trade agent David Thompson crossed the Rocky Mountains in 1807 and arrived at the Big Bend of the Columbia River, in the far north of our territory. He travelled south and east of Sinixt territory to reach the Columbia River’s mouth, then came upstream, arriving back in our territory in 1811.

In 1826, the British Hudson’s Bay Company established Fort Colvile beside the great Kettle Falls fishery. Here, traders captured the attention of the region’s many fine hunters, in particular, the Sinixt. In company records, our hunters appear frequently over the next decades, bringing in an outsized number of furs and hides, in trade for rifles, bullets, iron pots, knives, blankets and beads. This trade activity altered seasonal rhythms, and likely eroded traditional pit house culture in the 19th century.

European Disease and Missionary Conversions

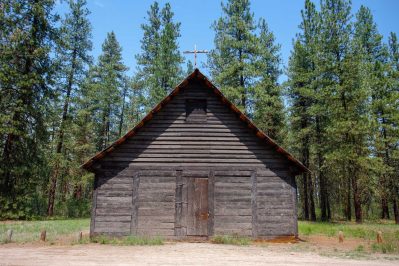

Measles, diphtheria and smallpox arrived even before the first European explorers, about 1780. Fresh waves of disease and epidemic continued to devastate our people, presenting great challenges to established healing practices. We sometimes turned to missionary conversions, often offered alongside vaccines. The first Catholic baptisms occurred in 1838, at Arrowhead on the Columbia River. Baptisms continued at St. Paul’s Mission, established in 1845 close to the trade fort and our fishing falls.

We have a long and complicated relationship with the Catholic Church. We are taught by our elders that all prayers are good.

We are now undertaking research to better understand our population prior to the arrival of European disease.

An Imposed Boundary, a Reservation and and a Forced Relocation

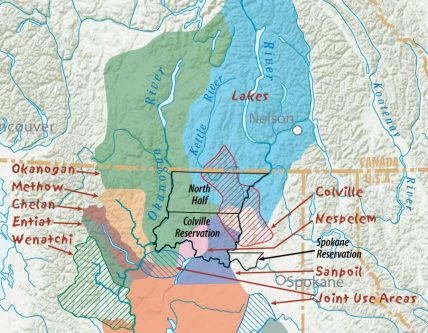

In 1846, the U.S. and Britain signed the Treaty of Oregon, setting the 49th parallel as the dividing line across our traditional territory. The British closed Fort Colvile in 1859 and opened Fort Shepherd a mile above the boundary, but “the trade” was gradually pulling out of the region. In 1872, a U.S. government executive order forced many Indigenous tribes onto the Colville Indian Reservation, a vast area on both sides of the Columbia River, stretching north to the new international boundary and east to Chewelah, WA.

The process of our forced relocation from Canada began when a British Columbia Indian Agent traveled through our territory above the boundary in the 1880s and did not notice some of us living there year round. No reserve was set up for us in our territory. Since the first days of settlement, the B.C. government had promised that they would set aside land for us at the confluence of the Kootenay and Columbia Rivers. Instead, they sold the land to settlers. Read more.

Sinixt people concentrated on the north half of the reservation lands, on the west side of the Columbia River up to the boundary, a place we call “Kelly Hill.” Gold-seeking, farming and settlement created more conflict. Some U.S. settlers claimed land inside these reservation boundaries. In 1891, pressured by mining interests, the government released the north half of the Colville Reservation to settlement.

Further Exile and the Murder of Cultus Jim

When we lost the North Half, many of us moved again, to Inchelium beside the Columbia River on the diminished CCT reservation. Some took allotments in or around Kelly Hill. Some intermarried with neighbouring tribes. A few left the region altogether. Sinixt people continued to travel quietly across the boundary to hunt, fish and gather in the traditional territory.

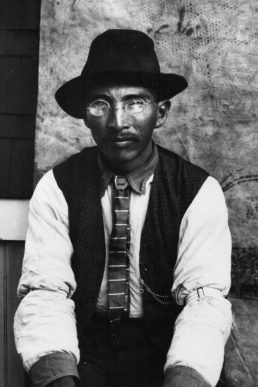

Settlers murdered our ancestor “Cultus Jim,” who had come to Galena Bay near Revelstoke with his wife Adeline. She ran to safety. Her son, William (Joe) Barr, recalls the event as she told him. Read an 1895 account of Adeline’s testimony through the eyes of colonial reporters.

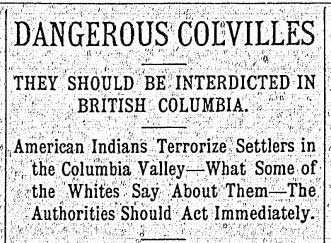

An 1895 newspaper article related to our hunting practices headlined “Dangerous Colvilles.” In response to our time-honoured hunting practices, British Columbia passed a law in 1896 , making it illegal for us to hunt in our territory.

Diaspora, Broken Promises and an Inadequate Reserve in Canada

Like many cultures around the world, we were experiencing a diaspora, or a ‘scattering’ from our traditional homeland. In addition, the historical events we faced led to a unique political extinction in Canada.

In Canada, the most racist piece of legislation the country has ever signed into law enforced cultural genocide on Indigenous people. The purpose of the Indian Act was to assimilate or eliminate Indigenous identities, through a ban on feasting and dancing, hunting and fishing in traditional ways or hiring lawyers to assert Aboriginal rights in court. These limits remained in place until the mid-20th century.

In 1902, 30 years after the U.S. government established the Colville Indian Reservation, the Canadian government finally announced the creation of the 200-acre Oatscott Indian Reserve. The land was mostly rocky and steep, with only a small strip of shoreline above high water. The remote location had no school, road access, medical care or grocery store. The 26 registered band members gradually drifted away, to be closer to extended family, reliable food resources and medical care.

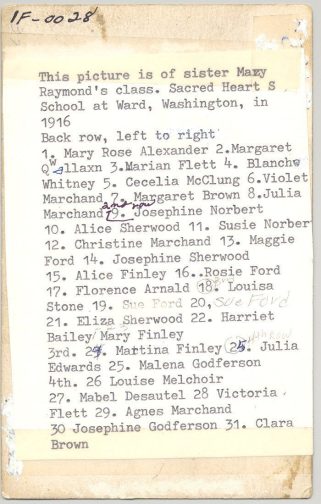

Indian Residential Schools run by churches and government agencies on both sides of the international boundary continued to harm the region’s tribes greatly, removing the Sinixt further from traditions.

This era was no time for an Indigenous tribe to assert its sovereignty.

Resilience and Retreat for Survival

Those of us living on the U.S. reservation nonetheless continued to travel north quietly, to hunt, or harvest fruit and roots in the pattern of our ancestors. Today we still carry reservation ID cards marked “Lakes” or “Arrow Lakes.”

We have always survived through cooperation and community, with resilience and endurance. We proved in traditional times that forming harmonious, peaceful villages and working together could help us thrive. We never lost our sense of identity as Sinixt. We know who we are.

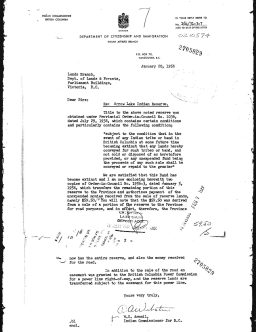

Indian Act Cruelty: A Declaration of Extinction

After the last listed member of the Oatscott Reserve’s Arrow Lake Band, Annie Joseph, died in 1953, the government diligently processed its paperwork. By 1956, it had returned the land and forestry assets to the province of B.C. and declared the Arrow Lake band to be “extinct.” At the time, several hundred of us were in refuge on the Colville Indian Reservation in Washington State.

Until the landmark decision in Desautel, the B.C. and Canadian governments treated the Sinixt as legally extinct. We had no recognized rights and after the 1956 map that they produced, found ourselves washed away from all official government maps.

A few years later, much of the reserve, a significant portion of our homeland and many burials were covered by water in a permanent flood from Columbia River Treaty dams. Read more about the Columbia River Treaty and its impact on our people in A River Captured: the Columbia River Treaty and Catastrophic Change.

Vallican Burial Disturbance

In the 1980s, government road repair and bridge-building disturbed ancestral burials. Sinixt people living on the Colville reservation crossed the border and set up a camp to halt further disturbance.

The provincial government initially refused to turn our ancestors over to us, because we were not recognized as Indigenous people in Canada – we were “extinct.” Our inability to rebury our ancestors is perhaps the greatest injustice of the extinction declaration.

The event reawakened our responsibility to protect our ancestors, and reminded us that the “imaginary line” of the international boundary needed to be addressed once and for all. We peacefully occupied the Vallican burial site for three full years and began the long process of correcting injustice and reclaiming our identity in our homeland.

The Desautel Case

After much careful consideration and years of discussion, the Colville Confederated Tribes decided to challenge the Canadian government’s “extinction” position. We sent Rick Desautel, a ceremonial hunter, north to hunt without a license, based on his right to hunt as a Sinixt Aboriginal Peoples of Canada.

After a 2016 trial confirming his rights, and three unsuccessful appeals by the province of B.C., the Supreme Court of Canada confirmed our Canadian rights with finality, on April, 2021.

Read more about the significance of the case, including transcripts of key moments.

This film by Sinixt artist and filmmaker Derrick LaMere, details the progress of the case through the Canadian courts, linking the resistance back to the Vallican burial disturbance.