Photo Credit: Shelly Boyd

Pre-Contact

Table of Contents

Traditional Governance

Sinixt Economy & Polity

Read this article by anthropologist Verne Ray to learn about how we governed ourselves and related to our neighbors.

Archaeology

Our traditional territory was physically remote by road and rail well into the 20th century, discouraging settler archaeologists from studying the region. Archaeology provides a limited understanding of our culture, but the following reports share interesting details about how and where we lived.

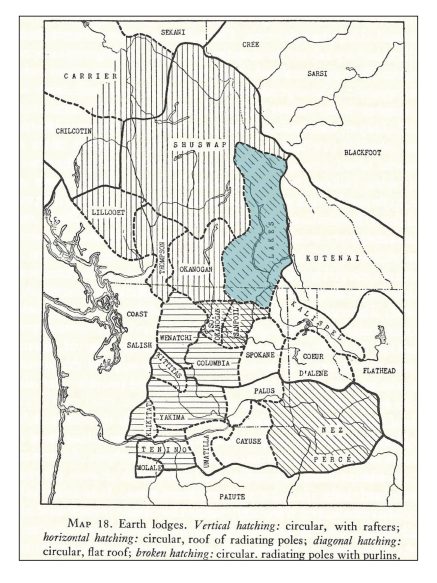

Pithouse villages were our way of surviving winter in the region. Tribal historian Richard Hart summarizes their importance, and our unique expression of them. (see Map 18).

Harlan Smith makes references to villages at Grohman Narrows, and to numerous seasonal camps along the West Arm of Kootenay Lake. His papers on file in the Canadian Museum of Civilization include notes about on-site research in the area in the 1920s .

The construction of dams and generating stations in the mid-20th century, followed by flooding of valleys by the Columbia River Treaty , greatly impacted the cultural record of our way of life. Traces of our homes, fisheries, burial grounds and spiritual practices have been flooded over and destroyed. Gordon Mohs did important salvage archaeology in the Arrow Lakes valley, and also wrote about Vallican, where the construction of a road threatened our burials.

Diana French conducted an archaeological investigation at Taghum, B.C. and identified signs of a pithouse village in Rosemont.

A traditional Sinixt dugout canoe was discovered submerged in the Kettle River just above the international boundary, in the 1970s. Michael Freisinger wrote two reports on Grand Forks and the upper Kettle River to Beaverdell.

Richard Baravalle explored and mapped extensive Sinixt pictographs on the east shore of Kootenay Lake.

Morley Eldridge produced a report on the Slocan Lake area.

In the 1980s, Craig Weir, a resident of Johnson’s Landing, discovered a rich deposit of stone tools and fragments on his beach near Johnson’s Landing. The retired journalist’s monograph mis-identifies the region’s Indigenous people as “Kootenay Indians” but offers an important local perspective on the story of stone tools. Our territory includes Kootenay Lake, the Purcell Mountains and the Lardeau and Duncan River valleys, a region we have more recently shared with the Yaqan Nukiy-Ktunaxa.

Nathan Goodale and Alissa Nauman have studied population dynamics at a Sinixt village site in the Slocan Narrows, near the mouth of Lemon Creek. The 40 pithouse depressions are of various sizes, one measuring 23 meters in diameter – the oldest this large yet discovered in the entire Interior Plateau. A total of 50 more known depressions are sprinkled further up the valley toward Slocan Lake, pointing to a healthy Sinixt population that relied heavily on salmon. Read some of Goodale’s published research.

Pictographs

In the Arrow Lakes, Slocan River and Kootenay/Trout Lake valleys, many examples of rock paintings from our people can still be seen. These spiritual expressions of our people are important and precious to us. The following illustrations of pictographs in our territory are taken from Pictographs in the Interior of British Columbia by John Corner. We are grateful for his preservation work.

Cultural Practices, pre-contact

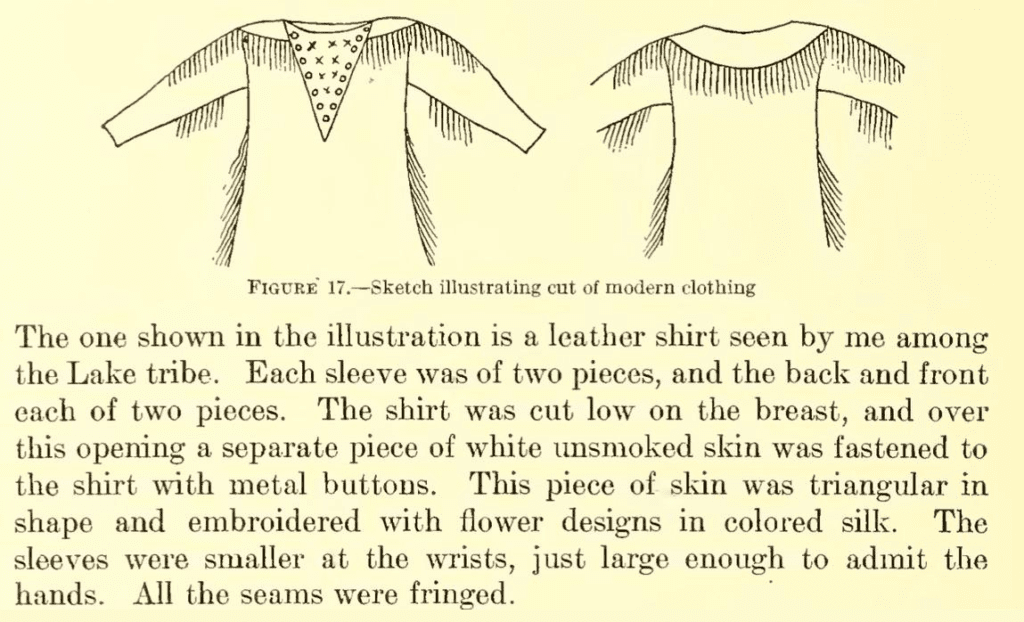

James Teit, an eminent Canadian anthropologist, gathered important information from Interior Salish tribes in the early 20th century. He published some of his research, edited by Franz Boas, in “The Salish Tribes of the Western Plateau,” part of the Forty-fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1927-28.

In the report, Teit classifies the Sinixt and several other unique tribes by similar language, using the term “Okanogan” in much the same way that the “English” language unites Americans, Australians, the British and Canadians.

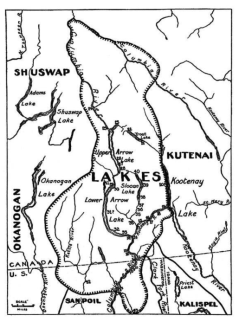

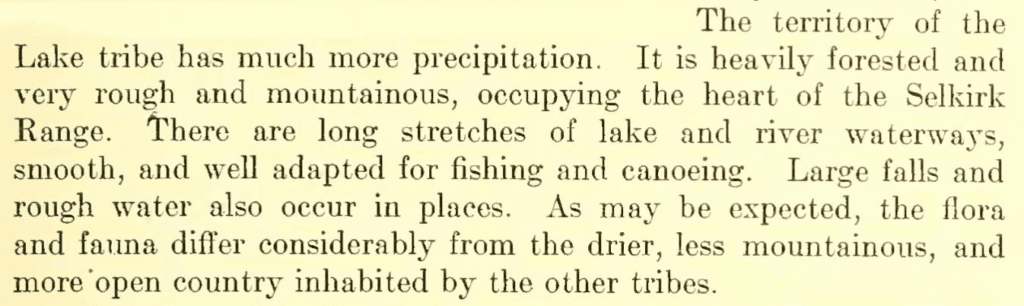

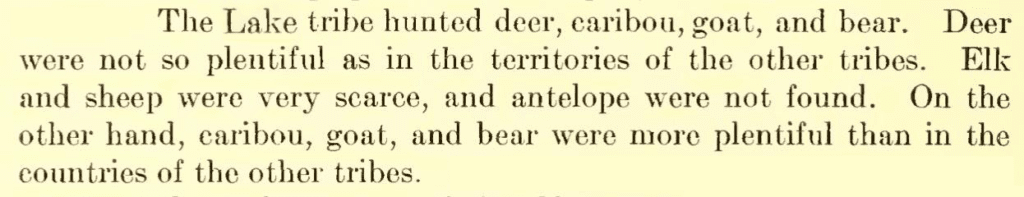

Teit travelled to and spent time in our territory, staying with our ancestors, the Christian family living at the mouth of the Kootenay River near Castlegar, B.C. In his research, he refers to our own name, and also as the “Lake Tribe,” because of our “habitat on the Lakes to the north, viz Arrow Lakes, Kootenai Lake, and Slocan Lake in British Columbia.”

Teit’s report respects our sovereignty and ties us closely to the region’s ecology, explaining that our name for ourselves refers to a unique cold-water fish, the bull trout, who we call “the “speckled trout.”

Bull Trout prefer cold, fast-moving water and deep lakes. A piscivore (fish that eats other fish), it is a powerful predator, prized to this day by fishermen for its firm, delicious flesh. Our ancestors fished for it year round.

For special occasions, we continue to wear ribbon shirts, dresses and other clothing that reflect our cultural pride. We are Lakes. We are Sinixt.

The Christian family explained the great importance of food preservation.

Teit’s information focussed on the Sinixt (pp. 198-250) is rich with respect. We are grateful for his work.