Photo of Kettle Falls, 1860

Honoring our Ancestors

Each of our ancestors carry important memories and knowledge. Some have been recorded in text form. All are remembered and treasured.

Table of Contents

19th Century

Nancy Wynecoop

Nancy Wynecoop (b. 1865), descended from strong leaders and good hunters. Her grandfather, Ske-owt-kin (Shadow Top, or, Tall Man) married Sepeetza (Able-One). The young couple followed the Columbia up “to its source,” Nancy recalled, “trapping all the while and living in a “tee pee of reeds. They had many of these teepees along the river. Instead of carrying [them] as the plains tribes did, they [rolled the mats and poles and] strung them up into trees so that when they came that way again, a home was waiting for them.” After her husband Ske-wt-kin died, Nancy’s grandmother Sepeetza“lived with us, clinging always to Indian customs. She preferred food cooking in “baskets by placing hot stones among the food. I can see her yet, lifting the hot stones with two sticks and dropping them into the baskets. We might prevail upon her to sleep in the house during winter, but as soon as spring came we would miss her. We always knew then that she had set up her teepee not far away and would remain there until winter snows drove her in.”With help from her daughter Nettie Wynecoop Clark, Nancy wrote down many memories and stories Sepeetza told her about the old ways. Wynecoop’s graceful memoir, In the Stream opens a window into the world of a Sinixt woman in traditional times, and also records several creation stories.

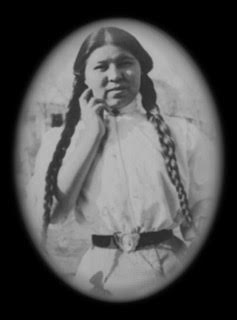

Agnes Christian Boyd

The daughter of Baptiste Christian, niece of Alex Christian, Agnes was born in the 19th century and travelled the transboundary Columbia with her family during an era in which settlers pushed the Sinixt further and further from their homeland. Baptiste and Alex Christian both resisted the Canadian government’s order for them to go and live on the Oatscott Reserve, located on the west shore of the lower Arrow Lake, dozens of miles upstream by canoe from Kp̓iƛ̓ls (Castlegar). The settler historical record mentions Alex Christian’s traditional hunting and fishing from Nelson to Trail; along the lower Kootenay and Slocan Rivers; and upstream along the Columbia as far as Deer Park and the lower Arrow Lake. The Christian family were the last Sinixt to live year-round in their traditional territory, protecting family burials and their lifestyle until about 1920.

While the Christians were ultimately forcibly removed from their territory, the correspondence they sent to the federal government in the early 20th century was used as power evidence that underpinned the 2021 win at the Supreme Court of Canada.

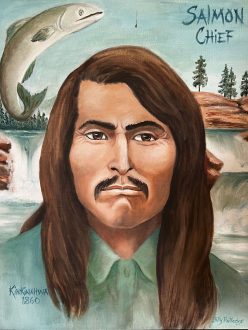

Salmon Chiefs

The work of Salmon Chief has always been to pray for the fish long at the center of our lives.

Kee-Kee-Tum-Nous was chief until 1862, when he died of smallpox.

Kin-Kan-Nowha was the chief who followed, as salmon numbers declined rapidly at the end of the 19th century from industrial fish wheels constructed downstream that were scooping up hundreds of thousands of returning spawners.

Chief Sipas received the power from Kin-Kan-Nowha in 1896 until about 1930. Even once settlers and governments built the dams, we continue to pray for the salmon.

20th century

William (J) Barr, b. 1909 in Northport, WA

His father was William Barr and his mother Adeline Barr. Adeline’s first husband was “Cultus Jim,” the man murdered by settlers at Galena Bay. Her son heard the story from her:“She must’ve been pretty young then, I guess, in her younger days anyway. They were out hunting…or taking a walk or something, they come to some guys that were working in a field…they were clearing land or something…they must’ve told them to keep away…she said one of the guys he had a coat held over a gun, he went and got the gun and shot him [Adeline’s husband], shot him and she ran, she ran away and she got away, they shot at her but they missed her.”

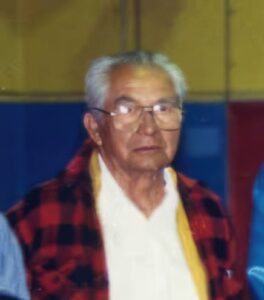

Charlie Quintasket, b. 1909 on Kelly Hill

The son of Joseph and Cecilia Quintasket, Charlie lived among many Sinixt relatives on the North Half, after the reservation boundary had moved south. In his seventies, he traveled to Victoria, B.C. to visit the museum and ask staff there why his tribe’s story had been ignored. In a 1986 interview, he recalls huckleberry picking on Red Mountain in B.C., starting when he was about 5 years old:

The son of Joseph and Cecilia Quintasket, Charlie lived among many Sinixt relatives on the North Half, after the reservation boundary had moved south. In his seventies, he traveled to Victoria, B.C. to visit the museum and ask staff there why his tribe’s story had been ignored. In a 1986 interview, he recalls huckleberry picking on Red Mountain in B.C., starting when he was about 5 years old:

“Every year, we’d all go up to Rossland, then at times we would go to Paulson [Blueberry Paulson summit of the Monashee Mountains] and then a place called State Road, just above the border, right along the border in fact….you go up to Christina Lake and there was a grade… angled back toward the border….And that was a popular huckleberry field too….when we went up to Rossland… we’d saddle up the horses, we’d pack out tents and all our baskets, food, what clothing we had and we’d move up there on what is now called Red Hill, it’s a ski area [now]… took over our huckleberry fields. We’d go up there and we would camp for about two weeks and after they had all the containers filled up that we could carry out, then they would dry them huckleberries, dry them out in the sun, same as you would raisins…huckleberry raisins. In the following winter you would steam that and it would come out pretty good, taste awfully good in the winter time. There was a lot of bear up there, even grizzlies but they didn’t bother people….”

He also shares his father’s astonishing memories of the scope of the Kettle Falls fishery in the 19th century, where 5-6,000 tribal people gathered from around the region:

“Kettle Falls, my Dad used to tell us about all the people that camped there, they come from far and near and there never was any trouble…although some were the traditional enemies from the Great Plains. Everybody was welcome there, there never was any trouble between the different bands because they come for one purpose and that’s to gather the dry salmon for the coming winters, to put the…food away….anywhere from five to six thousand Indians that gathered there during the salmon time….there was a Salmon Chief they called Kin-can-uch-wah, he was a very well known famous salmon Chief, and they [celebrate]…Chief Kin-can-uch-wah Days there at the falls…and then there was another one, either before or after his time they called him Sepas….”

Mary Marchand b. 1904, Kelly Hill

The granddaughter of Andrew Aurapahkin, a well-known Sinixt leader. Marchand’s mother Felicity was born near the mouth of the Pend d’Oreille River, right on the boundary. Her father William was born further west, right on the boundary at Cascade Falls. Marchand lived on Kelly Hill most of her life.

She recalls how her mother and another Lakes woman, Rosalie Seymour, traveled to gather traditional basketry materials:

“…my mother went with her, they went up to Boulder Creek and they picked the Cedar Roots to make the baskets. See they had to pick these green cedar roots, keep them wet…in big tubs and fill it with water…and she made the baskets. I got one of them…I was pretty thankful because I watched her make it. I’d come down to her house and watch her how she did it, It’s a hard work but she made that with her own hands….I’ll never forget her, she [could] do anything. Yeah, my mother went with her when she picked the roots up to Boulder Creek. They were always together, they traveled a lot.”

Marchand also recalls stories of her grandmother, Chief Andrew Aurapahkin’s wife, about ocean salmon spawning in the Arrow Lakes area in Sinixt territory prior to Grand Coulee dam:

“And the salmon goes clear up there, clear over to the end of that lake, my Grandma said in the fall when they all die off [on] the shores…that three hundred mile lake, was just nothing but dead salmon around the lake. See they all spawn there, then they die off…She said it just, just, you can walk along the shores, nothing but dead salmon, along the shores….”

Family stories of important ancestors are passed from generation to generation, with a pride and appreciation that informs contemporary work. Michael Marchand, tribal chairman and council member in the 1990s-2000s, remembers his father and two uncles:

Edward, John and Joe Marchand

By the end of the 1930s, the numbers of fish returning to Kettle Falls had declined greatly, but the traditional fishing continued. At times, state fish and wildlife officers, unaware of a government promise to the Sinixt and Skoyelpi that they could always fish at the falls, cut down tribal traps and hauled them away. They did this more than once, and it took the intervention of a Sinixt leader, James Bernard, to solve it. He telegraphed Washington DC and received an answer confirming the treaty right.

Edward, John and Joe Marchand, Mary Marchand’s sons, all who worked as fisherman at the falls, also served in WWII. When they returned from service, they found the time-honored fishery flooded by the water backing up behind Grand Coulee Dam.

No one had informed the tribes about the plans to flood their fishery. No one has since apologized.